Reevaluating Lee’s Leadership

In last month’s effort to critically evaluate Robert E. Lee’s leadership at Gettysburg, I argued that Lee’s orders lack clarity. U.S. Grant, in contrast, learned early in the Civil War, that simple, clear, lucid, unambiguous orders were critical to success on the battlefield. Often Grant wrote his own orders down, because it was quicker than explaining what he wanted to say. Meade’s chief of staff commented: “there is one striking feature of Grant’s orders; no matter how hurriedly he may write them on the field, no one ever has the slightest doubt as to their meaning or even has to read them over a second time to understand them.”

Lee’s Inadequate Staff

In re-evaluating Lee’s performance at Gettysburg, scholars have noted that Lee’s staff was too small and inexperienced for the responsibilities Lee bore. Outsiders argued that he should have more seasoned men, but Lee refused to take such men from their field assignments. One scholar noted: “In many respects, Lee was not a modern-minded general. He probably didn’t not understand the real function of a staff and certainly failed to put together an adequate staff for his army.” Even Douglas Freeman, who deeply admired Lee, argued that “surely no officer of like rank every fought a campaign . . . with only three men on his staff and not one of the three a professional soldier.” Staffers, in the tradition of the Napoleonic wars, were “drawn from friends or relations with no particular qualifications.”

What were some of the results of Lee’s Inadequate Staff?:

1. Having to handle the details of a large command, Lee was constantly tired. “Lee’s staff were not, in the modern sense, a planning staff — which was why Lee was often a tired general.”

2. Lee’s concept of duty argued, to his detriment and to the detriment of his leadership, that he “was to do things himself so as to see them done well.” He failed both to delegate and to build and train a capable staff worth delegating to. Twice, in the Overland Campaign, Lee even tried to led troops into the heart of battle, because he didn’t trust subordinates to do the job. Worried troops prevented him each time from leading them forward and possibly losing his life (and what they perceived as the hope of the Confederacy).

3. Without a strong staff, Lee also carried the weight of command by himself. And the stress of command may have contributed to his declining health and the advance of his congestive heart failure.

4. Lee often lost battlefield control. There were more than dozen times at Gettysburg when his orders were not obeyed — partly as we argued last month from lack of clarity. But, equally, because Lee did not have the staff to send to investigate or to follow-up on his orders. The scope of the battle was too large.

5. Lee trusted God and his men too much. That sentence was hard to write. In referring to Pickett’s Charge, one observer wrote:

“It was his most hazardous battlefield expedient yet, but then his men could do anything. Moreover, when he made any decision, success or failure lay not in his hands, but in His. If God meant for the assault to succeed, it would. If not, it did not. Lee and his staff sat their horses on Seminary Ridge and watched the mile-wide ranks of 12000 men go forward, but from that moment forward he made no effort to coordinate or direct the assault.”

6. While often seen as positive, Lee’s battlefield management philosophy only worked when his generals possessed the intuition of a “Stonewall Jackson.” His inadequate staff reinforced the flawed aspects of this approach. Lee said: “I plan and work with all my might to bring the troops to the right place at the right time; with that I have done my duty. As soon as I order the troops forward in battle, I lay the fate of my army at the hands of God. It is then my General’s turn to perform their duty.” The strategy worked with Jackson at Chancellorsville, but at Gettysburg– everyone was confused by Lee’s “presence and absence.” Lafayette McLaws, division commander under Longstreet, observed that at Gettysburg: “the disjointed assaults which could not under any circumstances have produced favorable results, have not yet been explained.”

Part of the explanation might be Lee’s lack of personal and professional staff.

Grant’s Counter Example

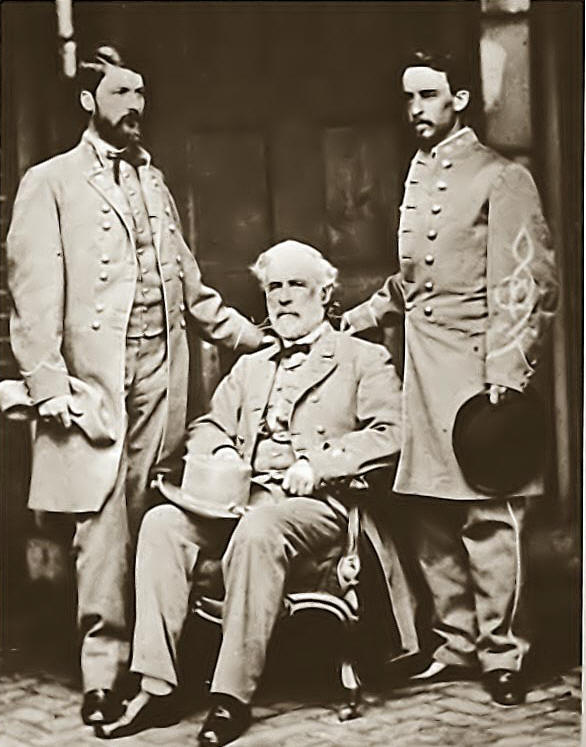

Again U.S. Grant offers a counter-example as this one of many pictures of Grant’s staff suggests.

Lee’s staff were mostly lieutenant colonels, operating as not much more than glorified clerks. Grant’s staff, which included generals, “was an organization of experts in the various phases of strategic planning.”

During battles, Grant often sent members of his personal staff as his emissaries or as his alter egos to far sectors of the battlefield–even to other theaters. At Shiloh, one of Grant’s aides was positioning artilllery, another herding troops to the right area and two others were sent to get Lew Wallace’s division into the fight.

Grant constantly expanded the duties of his personal staff and constantly delegated responsibility. Grant found a creative way to use his personal staff, making them “his right hand of command.”

Few of us in ministry work lead organizations large enough for “personal staffs.”

Nevertheless, what might be the lessons we can draw from Lee’s use of staff?

Are you carrying the burden of leadership alone?

Who serves as “your right hand of command?”

In what ways do you surround yourself with expertise?

Are you “trusting God too much”? In other words, are you doing everything you can to win (and then trusting God)?

Who is helping you “see and embrace” reality?