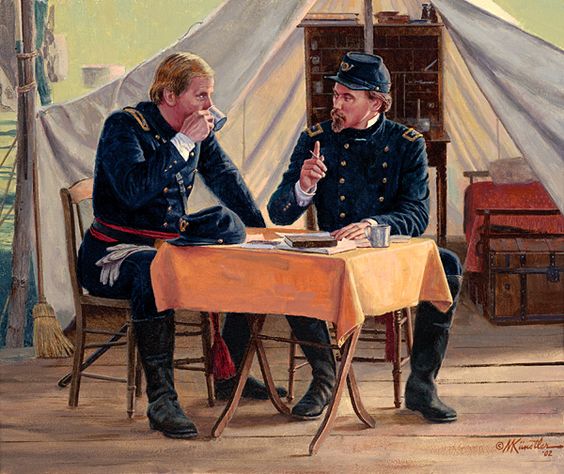

I don’t know anything about military tactics. But I know how to learn. I study, I tell you every military work I can find. And it is no small labor to master the evolutions of battalion and brigade. I am bound to understand everything. And I want you to send me my Jomini Art of War. The Col. and I are going to read it. He is to instruct me, as he is kindly doing in everything now.–Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain to his wife

I’m intrigued by this portion of a letter Chamberlain wrote to his wife soon after he left Bowdoin College to help form the 20th Maine regiment.

In an article for Harvard Business Review, Erika Andersen describes people who succeed at learning. Chamberlain was no doubt, one of those.

But I Know How to Learn

People who succeed at learning have four attributes: aspiration, self-awareness, curiosity, and vulnerability.

They truly want to understand and master new skills; they see themselves very clearly; they constantly think of and ask good questions; and they tolerate their own mistakes as they move up the learning curve.

Aspiration–“I am bound to understand everything.”

It’s easy to see aspiration as either there or not: You want to learn a new skill or you don’t; you have ambition and motivation or you lack them. But great learners can raise their aspiration level—and that’s key. When we do want to learn something, we focus on the positive—what we’ll gain from learning it—and envision a happy future in which we’re reaping those rewards. That propels us into action.

Self-Awareness–“It is no small labor to master the evolutions of battalion and brigade. . . Send me my Jomini.”

There is a lot of emphasis on self-awareness. We understand that we need to solicit feedback and recognize how others see us. But when it comes to the need for learning, our assessments of ourselves—what we know and don’t know, skills we have and don’t have—can still be woefully inaccurate. Last month, we talked about the vulnerability of the leader and how critical it is to adopt a learning posture and stay committed to learning for a lifetime.

Curiosity–“I study, I tell you every military work I can find.”

Kids are relentless in their urge to learn and master. Curiosity is what makes us try something until we can do it, or think about something until we understand it. Great learners retain this childhood drive.

Vulnerability–“I don’t know anything about military tactics. The Col . . . is to instruct me.”

Once we become good or even excellent at some things, we rarely want to go back to being not good at other things. . . So the idea of being bad at something for weeks or months; feeling awkward and slow; having to ask “dumb,” “I-don’t-know-what-you’re-talking-about” questions; and needing step-by-step guidance again and again is extremely scary. Great learners allow themselves to be vulnerable enough to accept that beginner state. In fact, they become reasonably comfortable in it.

Related Idea:

Leaders Must Adopt a Growth Mindset

Mindset is a simple idea discovered by world-renowned Stanford University psychologist Carol Dweck in decades of research on achievement and success—a simple idea that makes all the difference.

In a fixed mindset, people believe their basic qualities, like their intelligence or talent, are simply fixed traits. They spend their time documenting their intelligence or talent instead of developing them. They also believe that talent alone creates success—without effort. They’re wrong.

In a growth mindset, people believe that their most basic abilities can be developed through dedication and hard work—brains and talent are just the starting point. This view creates a love of learning and a resilience that is essential for great accomplishment. Virtually all great leaders–like Chamberlain–have had these qualities.