In his excellent book, Strong and Weak: Embracing a Life of Love, Risk and True Flourishing, Andy Crouch argues that leaders need both authority (the ability to act meaningfully) and vulnerability (an exposure to true risk and loss).

He calls the tension between authority and vulnerability–the drama of leadership. As leaders we by definition have authority, but to lead well and to flourish, we must also bear hidden vulnerability–the weakness and risk that no one else sees.

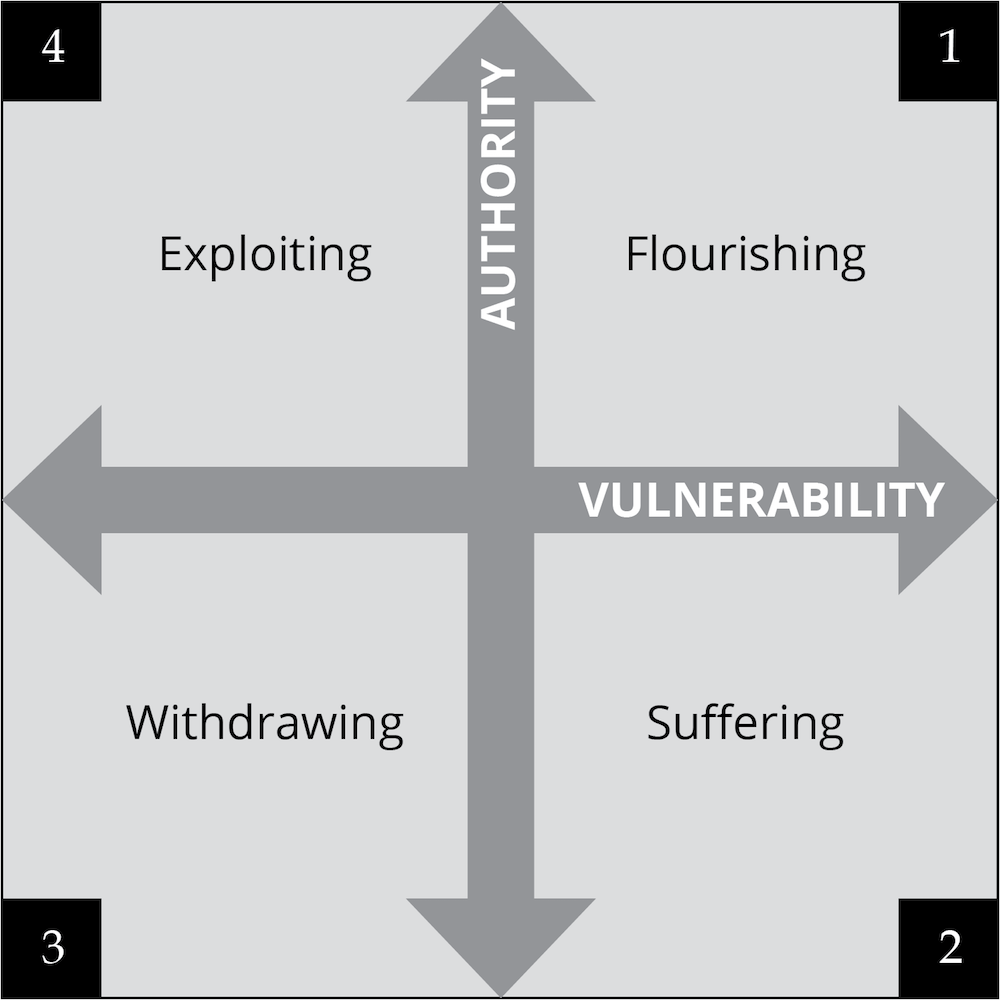

As the 2 x 2 diagram above shows, flourishing as a leader comes from being both strong and weak—from authority balanced by vulnerability.

(Andy Crouch loves 2 x 2 matrixes and I’m increasingly using them at Gettysburg to explain what often appear as opposable ideas. See a post I did years ago on Integrative Thinking—where we develop the ability to face constructively the tension of opposing ideas and, instead of choosing one at the expense of the other, generate a creative resolution of the tension in the form of a new ideas that contains elements of the opposing ideas but is superior to each. i.e. Evangelism and Discipleship, Gospel Proclamation and Gospel Demonstration, Courage and Care, Gospel Courageous and Gospel Corrective Leadership.)

Crouch’s 2 x 2 matrix creates four quadrants in which we as leaders and leader-makers have a tendency to live, depending on our capacity for authority and vulnerability.

In quadrant 4, authority is high and vulnerability is low. As a result, leaders exploit others by seeking to maximize power while eliminating risk.

In quadrant 3, leaders (in name only) possess neither authority nor vulnerability, they withdraw. They isolate themselves. They opt for safety. They fail to lead.

In quadrant 2, opposite from exploiting, with high vulnerability and low authority, leaders default to suffering. No will to change is present.

Quadrant 1, however, is where flourishing as a leader happens—at the intersection of true authority and true vulnerability.

Crouch writes: “In a world where many people simply withdraw into safety, where others are imprisoned in the most extreme vulnerability, where others pursue their own unaccountable authority, anyone who seeks true flourishing is already, in many senses, a leader.”

Lots of ideas about leadership arise from the creative tension of authority and vulnerability.

1. True leadership (see last month’s article on Gen Ewell at Gettysburg) arises perhaps unexpectedly from the vulnerability or exposure to true risk and loss. Withdrawing or “being safe” (the fear of failure, the fear of suffering and loss) handicap our ability to lead. As Simon Sinek defines leadership–the leader is always the first person to step out in a new direction, the first to seize opportunities, to accept risk.

2. Vulnerability makes us teachable. Our authority moves from exploitation to exploration. It keeps us from overconfidence, while fueling that balance between confidence (moving boldly in a direction we’ve decided on) and humility (acknowledging that your decision is only an educated guess). We can embrace what’s really happening.

3. Last April, we discussed in this letter–how unexpectedly “vulnerability” was part of the Navy Seals culture. Dave Cooper of Elite Team Six says: the success of the Seals lies in a culture of vulnerability. “It all begins with the leader’s willingness to say the four most important words any leader can say: I screwed that up.” As he or she does so, the team develops a willingness to spot and confront the truth. Great teams come together to ask a simple question over and over: What’s really going on here? As the leader is vulnerable, the rest of the team becomes vulnerable.